A six-foot-high bronze sculpture of an elegant woman in high heels graces the entrance lobby of the Iowa Memorial Union. Since 2007, the sculpture has dignified this space, exuding confidence among University of Iowa students who study there.

“I suspect that people walk by and don’t realize what they’re seeing,” said Susan Boyd, Iowa City art supporter and wife of former University of Iowa President Willard “Sandy” Boyd.

This sculpture—titled Stepping Out—was created by University of Iowa distinguished alumna Elizabeth Catlett, who was among three UI students to earn the first Master of Fine Arts (MFA) degrees in the United States in 1940. She also was the first African-American woman to receive an MFA.

Catlett died April 2, 2012 at her home in Cuernavaca, Mexico. She was 96.

“She was a huge proponent of building self-esteem, especially during the black feminist movement,” says Kathleen Edwards, chief curator of the University of Iowa’s Museum of Art. “As a sculptor and printmaker, she was probably the most important female African-American artist in the United States.”

Catlett discovered her artistic passion as a graduate student at the University of Iowa. She studied drawing and painting with Grant Wood—painter of the iconic “American Gothic”—and sculpture with Henry Stinson during an era that saw new racial openness, even while aspects of segregation continued.

While at Iowa, Catlett received advice from Wood that influenced her entire artistic career.

“Grant Wood was a very generous teacher, and he influenced all my work,” Catlett said in a story published in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences’ Arts & Sciences magazine in 2003. “He would tell his students, ‘Paint what you know.’”

Taking her teacher’s advice to heart, Catlett depicted black women as strong, maternal figures. Catlett’s graduate thesis project, a stone carving of a black mother and child, earned first prize in Chicago’s 1940 American Negro Exposition.

“She’s one artist we should be really proud of; the University should be proud of its connection to her,” says Claire Fox, a UI associate professor of English who co-teaches a Latin American Studies course that includes a section on Catlett’s work. “She has had a profound influence on a generation of artists.”

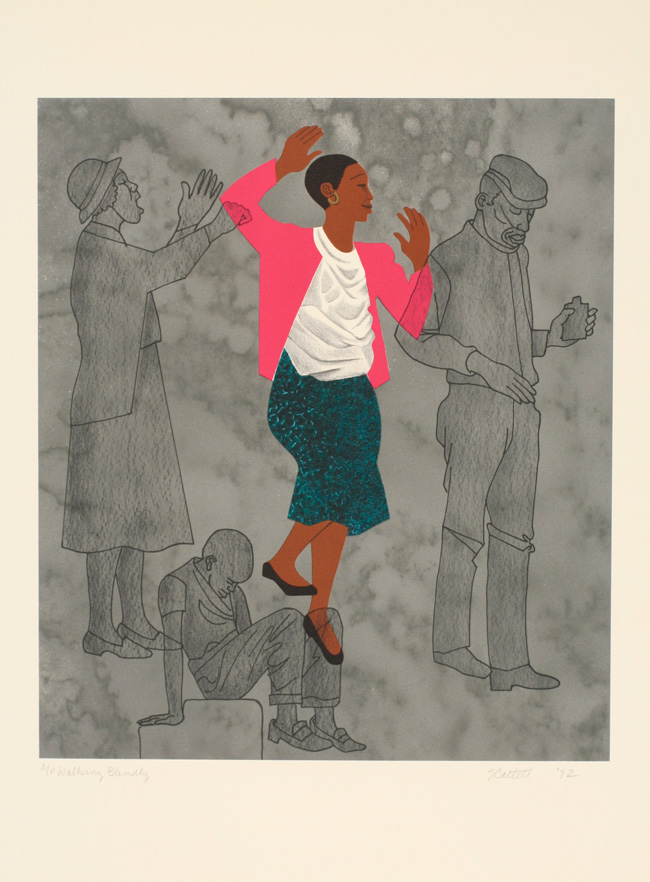

In 2006, UI curator Edwards visited Catlett in Mexico, where she lived since 1946, to work as a guest artist with the Taller de Grafica Popular (TGP) and later that year moved to Mexico for good. Edwards purchased 28 Catlett prints for addition to the UI Museum of Art’s permanent collection.

Catlett, in turn, donated the purchase price of the prints to the University of Iowa Foundation to create the Elizabeth Catlett Mora Scholarship Fund.

“She was an example to students, in terms of her life and the choices she made, to stick to your own ideas about what you want to pursue,” Edwards says.

Joshua Dailey, an MFA candidate in the UI School of Art and Art History’s printmaking program, is a proud recipient of an Elizabeth Catlett Mora Scholarship, which is awarded to an undergraduate or

graduate student in printmaking who is African-American or Latino.

“It’s really inspiring to look at someone who was so whole-heartedly devoted to activism, using her work as a vehicle to promote social change,” says Dailey, a Dean’s Graduate Research Fellowship recipient. “The thing that immediately strikes me about her work is its accessibility. Her work served the African-American community, and conveys the human message as well.”

Jaime Knight—an MFA candidate in art and a Catlett Mora Scholarship winner—expresses an appreciation for Catlett and her ties to the UI.

“I really love her dedication to the program here,” says Knight, also a Dean’s Graduate Research Fellowship recipient. “It is evident she found printmaking to be an integral part of her practice despite being mostly recognized as a sculptor.”

Confident that her art could influence social change, Catlett, the granddaughter of freed slaves, focused on her own ethnic identity, and its association with slavery and class struggles.

At Iowa, Catlett faced segregation first hand when she was forced to rent a room in a local home since African-American students were not allowed to live in University residence halls at the time. The UI, however, allowed her to attend school, while the Carnegie Institute of Technology earlier had denied her undergraduate admittance because she was “colored.”

“During her time, it was not easy for an African-American woman to attain a quality arts education,” Fox says. “She faced obstacles on campus, but on the other hand, she had a productive relationship with Grant Wood.”

In 2002, Iowa purchased Catlett’s first major print—“Sharecropper”— which shows a white-haired black woman with sharp features and a serene gaze. Susan Boyd helped raise money to purchase the painting.

“There was something so dignified and so hard-working about that woman in ‘Sharecropper,’” says Boyd, who never met Catlett, but spoke with her on the phone after the UI purchased the print. “This woman has this safety pin on her clothes, but there is an elegant look about it. There was something that spoke to me in that painting.”

Catlett’s artwork has spoken to many people over the last half-century.

“I thought she was very good with what she did. There was form to it, there was passion to it,” says Wallace Tomasini, UI professor of art history. “She did what she loved.”

In 1996, the UI Alumni Association awarded Catlett a Distinguished Alumni Award, which recognizes significant accomplishments in business or professional life or for distinguished human service.

“She was always so anxious to help young people be encouraged. That was terrific,” Boyd says. “Now that there is increased interest in her at the time of her death, I hope we realize that we have a really significant sculpture in the Iowa Memorial Union.”